Just before spring break, an assembly was held a Verona High School about Ugandan rebel Joseph Kony and his forced conscription of child soldiers. Intended to provoke discussion about international affairs, the program has also prompted some soul-searching within the public school district about the place of assemblies in the education system.

Just before spring break, an assembly was held a Verona High School about Ugandan rebel Joseph Kony and his forced conscription of child soldiers. Intended to provoke discussion about international affairs, the program has also prompted some soul-searching within the public school district about the place of assemblies in the education system.

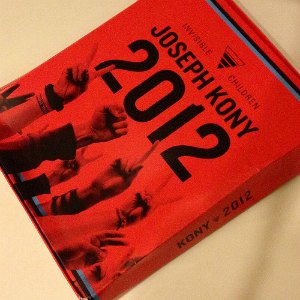

In case you missed the video that went viral on YouTube in March, a U.S.-based non-profit called Invisible Children created a mini-documentary, Kony 2012, about its efforts to track down Kony for arrest. The group intended to harness the power of social media to put increased pressure on African and international officials to capture Kony. It did, getting more than 89 million views of the video, instead of the 500,000 it had anticipated. Invisible Children also, however, found itself ensnared in questions about its film making and finances. Those questions grew louder after Jason Russell, Invisible Children’s co-founder and the director of Kony 2012, was detained by San Diego police after suffering an apparent breakdown in public.

Since Invisible Children made its first movie about Kony in 2003, the group has spoken to hundreds of schools and colleges around the United States, often selling merchandise and soliciting donations at those locations. Prior to approving the assembly, VHS officials had travelled to Bergen County to see one at a high school there. But as word of the impending assembly filtered out, the emails and calls to the school and the Board of Education began coming in. Why, many asked, was the school taking students out of class for a potentially flawed assembly–all VHS students were scheduled to see the presentation–when there was so much other teaching to be done? How many assemblies do our schools hold and how much classroom time is lost? Why is fundraising for causes that have nothing to do with education being done on school time?

The questions spilled into the BOE meeting on April 10 where, it turned out, there were few answers. Decisions on assemblies are made by individual building principals, and no tallies are kept on how many hours are spent out of class on them. There is no overall policy on what fundraising may or may not be done on school property for non-school programs: The American Heart Association has been running its Jump Rope For Heart event at H.B. Whitehorne Middle School for 15 years. While that raises thousands of dollars for the AHA the group does not compensate HBW for the use of its facilities or staff time spent on the event, which it would have to do if it were booking a private venue for an event. And it’s not just assemblies: the board noted: The day of the Kony assembly, the entire VHS band would be out of school for a performance at the Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark.

With teachers under pressure to deliver an ever more rigorous curriculum and the new superintendent looking to add instructional time for science and technology, the questions are not arcane. Verona’s new superintendent, Steven A. Forte, pledged to gather an accounting of time spent on assemblies and field trips for a future board meeting.

With teachers under pressure to deliver an ever more rigorous curriculum and the new superintendent looking to add instructional time for science and technology, the questions are not arcane. Verona’s new superintendent, Steven A. Forte, pledged to gather an accounting of time spent on assemblies and field trips for a future board meeting.

The Kony assembly, meanwhile, proved thought-provoking for many students. For Kyle Thomas, a junior who already helps with many community service projects at Our Lady of the Lake, it was an eye-opener into non-profit finance. In investigating Invisible Children he discovered that it spends only about 34% of the money it raises in Uganda. “Average citizens can’t go across the sea to help, but we can send money,” he said. “But if I send them money I expect that to be used for the actual cause and not to tell everybody else about it.” He asked questions at the assembly and learned he could write a restricted check that could be used only in the African nation. “I still support the cause I question how they are carrying it out,” he added.

Shannon Garner, a senior, came away thinking about helping as well. “We usually have one heart-breaking assembly a year,” said Garner, who introduced the program in her role as student body co-president. “Freshman year, we had prisoners from county jail talk about how not to be like them. Sophomore year it was a cyberbullying case that ended in a suicide. That made a few kids cry.” Already active in outreach programs here, she plans on doing more volunteering for Africa when she heads to college in the fall: James Madison University offers alternate spring breaks to Africa, where students can give food, water and medicine to needy children.

Kony poster photo by informatique via Flickr

Photo this page by G4Gti via Flickr